BUG OF THE MONTH: August 1998

Hollyhock Weevil

Apion longirostre

Order Coleoptera, Family Curculionidae

Copyright © 1998 by Louise Kulzer

This article originally appeared in Scarabogram, August 1998, New Series No. 220, pp. 2-4.

One of the garden delights of high summer is the hollyhock. Although most gardeners know of the hollyhock's proclivity toward rust, preferring instead to concentrate on the colorful twirls of flowers, few realize that other more interesting pests are probably walking around right under their noses. For the hollyhock weevil is a delightful Lilliputian creature that makes its living largely unnoticed on this colorful garden shish-kebab.

|

|

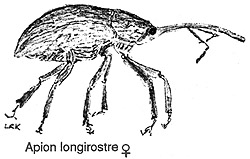

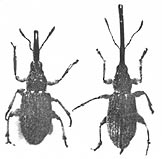

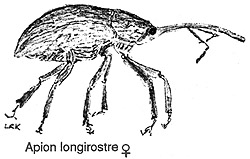

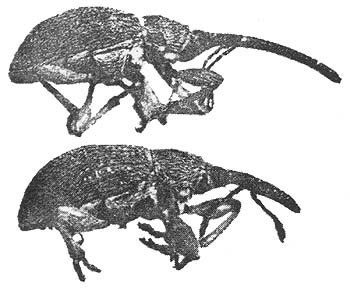

| Adult female hollyhock weevil | Male (left) and female (from Ehret) |

The hollyhock weevil is not often noticed because it is so small. Mine measured in a bit over 4 mm (about 1/8 inch). The amazing thing about this weevil is not its small size, however, but the length of its snout. It looks for all the world like the weevil equivalent of an elephant! When measured, the male snout is about half as long as the total body length...and even longer in the female. But in action, I swear the snout seems almost as long as the body itself! A wondrous sight indeed! [Sometimes longer then the rest of the body in females, according to Hatch.]

|

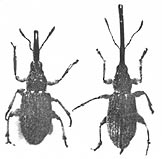

| Female (above) and male hollyhock weevil (from Tattersall & Davidson 1954) |

Like most weevils, the hollyhock weevil is a plant feeder. Both sexes use the long proboscis to eat seeds, buds and leaves of hollyhock (Cranshaw 1992). On my hollyhock, I've only seen them on the flower buds, not on the leaves, but I haven't checked on them at night.

So why does the female of this creature have a longer snout than the male? The female lays her eggs in early summer in the developing flower buds. So the female needs a snout long enough to chew down to the ovary within the developing bud and there lay her eggs. Hence her need for the extra length. After the eggs hatch, the larvae eat the developing seed embryo, and pupate within the seed. Cranshaw (1992) reports that some of the pupae emerge in late summer, and some the following spring.

But back to snouts. The real question is what the males eat, isn't it? Do they eat into the buds too? If so, one can see that a long snout would be an asset. But if they only eat leaves, there is really no need for a long snout, now is there? Maybe it's a sympathetic evolutionary gesture to make the females feel less conspicuous? A little scientific observation seems in order, doesn't it?

Overall, I think that having hollyhock weevils is akin to having lovebirds in the garden - a sensual delight! I can attest to the fact that the weevils mate frequently and the sexes appear to get along amicably. However, if you are picky about the appearance of your hollyhock, or if you have too many weevils, some ideas for control are (1) to pick the seed pods, preventing the immatures from emerging or (2) shake the hollyhock stalk over a sheet. The adults will drop off onto the sheet where you can squash them or collect them for friends, depending on your sensitivity.

Go forth; seek hollyhock weevils. Savor the small delights of summer along with the large!

[Some additional info: "A species native to southern and southeastern Europe and Asia Minor. It was first taken in North America in Georgia in 1914 and is now widespread over the United States. The species was first taken in the Pacific Northwest in 1966 at Soap Lake, eastern Washington" and seems to be spread in hollyhock seeds (Hatch). The species is also still expanding its range in Europe, having only recently been found in France (Ehret 1983); it is also now found as far east as Afghanistan and as far north as Poland (Perrin 1984). According to Tuttle (1954), both males and females feed from unopened hollyhock buds; mate in late July and August; larvae develop in 4-6 weeks and pupate around the end of August; most overwinter as adults. Hollyhock is the only known food plant. Adults feeding on leaves make small round holes; "the female drills through the calyx and petals of the buds with her long rostrum and then oviposits in the cavity. While ovipositing, she is usually surrounded by several males." (Tattershall & Davidson 1954)] --editor.

References

Cranshaw, Whitney. 1992. Pests of the west: prevention and control for today's garden and small farm. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing, xiii + 275 pp.

Ehret, J.M. 1983. Apion (Rhopalapion) longirostre, espèce nouvelle pour la France (Coléoptère Curculionidae). L'Entomologiste (Paris), 39(1): 42.

Hatch, Melville H. 1971. The Beetles of the Pacific Northwest, Part 5, p. 329. University of Washington Publications in Biology vol. 16.

Perrin, H. 1984. Presence in France of Apion (Rhopalapion) longirostre Olivier (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Apioninae) and distribution in the Palaearctic Region. L'Entomologiste (Paris), 40(6): 269-274.

Tattershall, John T., and Ralph H. Davidson. 1954. Life history and control of Apion longirostre Olivier. Journal of Economic Entomology, 47(1): 181-182.

Tuttle, Donald M. 1954. Notes on the bionomics of six species of Apion. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 47(2): 301-307.

This page last updated 26 July, 2005