BUG OF THE MONTH: October 1996

The European Earwig

Forficula auricularia

Order Dermaptera, Family Forficulidae

Copyright © 1996 by Louise Kulzer

This article originally appeared in Scarabogram, October 1996, New Series No. 198, pp. 2-4.

|

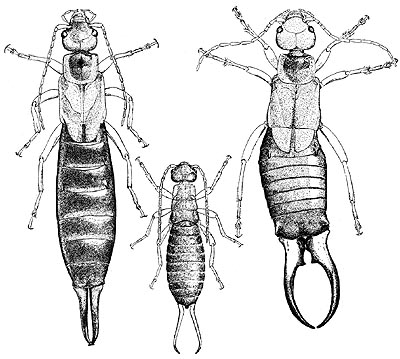

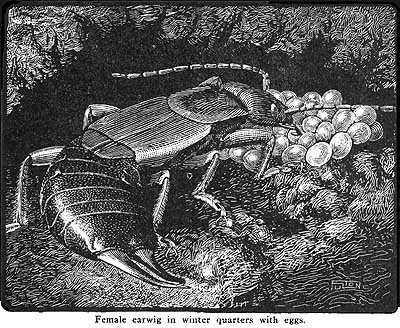

| Female, 3rd instar nymph, and male of European earwig |

Four species of earwigs are reported in the Puget Sound area (Crawford 1985). Three are rare, one quite common. The common one, Forficula auricularia, is the European earwig, an almost ubiquitous inhabitant of gardens around the area. I must admit that this may be one of the few bugs I dislike, considering the damage they inflicted on my tender clematis shoots this summer. Nonetheless, earwigs are interesting in an intellectual sort of way.

To the casual observer, the most noticeable thing about earwigs is their cerci, which are developed into a very functional pair of pincers or forceps. The forceps are used to capture prey, defend the nest from intruders and in some species, to help fold or unfold the wings and in mating. The European earwig uses the forceps more sparingly than in other species. Most of the prey they take is rather easily subdued and eaten while held only with the front legs without need for the forceps (Fulton 1924). Although it's seldom seen to fly, the forceps have been observed to aid in tucking the membranous hind wing back under the short, leathery fore-wing (op. cit.). When dispersing, they can actually fly long distances, but probably do so at night (Crawford, personal communication). Those who handle earwigs over-much can attest to the effectiveness of the forceps! I've even heard reports of blood being drawn by an earwig pinch, although in fairness they mostly don't pinch at all.

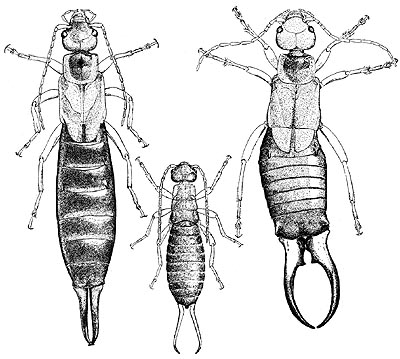

Earwigs' main claim to entomological fame is not, however, their forceps. It is their care of the eggs and young that fascinate many entomologists. Earwigs are subsocial insects, meaning that there is parental care of the young, but not cooperative brood care. The nest of the European earwig is a short tunnel dug in the ground or a natural cavity, often adjacent to a rock. Most commonly, the nest has two chambers (Lamb 1976). Males may occupy nests with females for a short time (the honeymoon, so to speak), but are expelled after the eggs are laid. In a colony of European earwigs raised by Fulton (1924), the males were never observed to dig cavities for themselves, but used existing crevices "no matter how poor the accommodations." Funny how some behaviors are conserved over evolutionary time, huh?

The female very actively busies herself with the eggs, and unlike Hymenoptera which pretty much leave the eggs alone until they hatch, earwigs clean the eggs often and re-pile them. The female may even move them to different parts of the tunnel. Eggs are often moved in contact with a stone, if indeed the nest is adjacent to a stone surface. Lamb (1976) hypothesized that movement of the eggs may be for temperature regulation, but this has not been shown conclusively.

Eggs that are not tended have a much lower survival rate than eggs that are

tended. If the female is not present, the eggs are soon attacked by mold. Females

not only clean mold off the eggs, but deposit a fluid on the egg as well (Lamb

1976). They do not seem to recognize the eggs as distinctly their own, but will

tend eggs or even foreign objects introduced into the nest. Damaged eggs are

eaten.

tended. If the female is not present, the eggs are soon attacked by mold. Females

not only clean mold off the eggs, but deposit a fluid on the egg as well (Lamb

1976). They do not seem to recognize the eggs as distinctly their own, but will

tend eggs or even foreign objects introduced into the nest. Damaged eggs are

eaten.

The female defends her nest vigorously, but if the nest is disturbed repeatedly, she will eat the eggs and abandon the nest. European earwig females usually do not feed while tending eggs, and often she seals the nest entrance as an added defense against intruders. I guess all that egg mold ruins her appetite!

After the eggs hatch, the nymphs remain in the nest for a time (remember, earwigs are hemimetabolous, so the young are nymphs). They are fed by the female but also begin to forage for themselves early on. The female brings food back to the nest for the nymphs but also regurgitates food, a fact established by Shepard et al. (1973) by radioactive labeling. If the young of another earwig enters the nest, the female accepts it as her own, just as any young of hers that wander into another nest will be equally accepted. Entomologists say this is because the females don't discriminate between their own and another's young (Fulton 1924). But really, I think it's the evolutionary beginnings of baby-sitting co-ops.

After the nymphs leave the nest, usually sometime in the second instar, the female no longer cares for them, nor indeed, shows any specific reaction to her young (Lamb 1976). (I kind of like that approach too.)

Now all this nesting stuff begins in the spring, and since multiple broods are typical, continues throughout the summer. Females may mate again after the first brood, but do not have to for fertile eggs to be produced (Lamb 1976). Guess they do it for fun, huh?

Now, one question I have is how do sowbugs and earwigs get along? After all, they seem to coexist in the same environmental niche. Well, in Fulton's colonies, sowbugs were largely ignored by earwigs, mingling with the nest inhabitants without being driven off as most intruders were. However, earwigs will readily eat dead sowbugs. But of course, they will eat dead earwigs too. Intriguing, huh?

Speaking of eating, earwigs are omnivores, which means they eat both plant and animal matter. They are often pests of potatoes and grain, but in my garden they also like flower petals (roses in particular) and relish the new shoots of clematis, as I complained about earlier. Bharadwa (1966) suggests a bait of bran, molasses and Paris green in water for earwig control. Now if I just knew what Paris green was, I'd have a happier clematis! [It's a crude form of arsenic.--editor]

Oh yes. The other local earwigs are wingless Anisolabis maritima, the seaside earwig, which is found on salt water beaches and shaped a bit like a person in a mummy-type sleeping bag; Labia minor, a tiny wee earwig (which flies readily); and wingless Euborellia annulipes, the ring-legged earwig, which tends to be limited to warehouse and greenhouse locations in our area (Crawford 1985), but is more common in the midwestern and southern US. (Bharadwa 1966).

Next time you see earwigs, remember that sowbugs have made their peace with them. Maybe it's time for you to as well, especially if you know what Paris green is!

References

Bharadwa, R.K. 1966. Observations on the bionomics of Euborellia annulipes (Dermaptera: Labiduridae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 59(5): 441-449.

Crawford, Rod. 1985. More on earwigs by the editor. Scarabogram, New Series No. 68, p. 2. November, 1985. [with all 4 spp. illustrated]

Fulton, B.B. 1924. Some habits of earwigs. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 17: 357-367.

Lamb, Robert. 1976. Parental behavior in the Dermaptera with special reference to Forficula auricularia (Dermaptera Forficulidae). Canadian Entomologist, 108: 609-619.

Shepard, M., V.Waddil, and W. Kloft. 1973. Biology of the predaceous earwig Labidura riparia (Dermaptera: Labiduridae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 66: 837-841.

This page last updated 26 July, 2005