BUG OF THE MONTH: June 1997

Indian Meal Moth

Plodia interpunctella

Order Lepidoptera, Family Pyralidae

Copyright © 1997 by Louise Kulzer

This article originally appeared in Scarabogram, June 1997, New Series No. 206, pp. 2-3.

Well, well. Now I know who you are! I beg your indulgence, kind reader, but after years of cohabitation, I've finally learned the identity of my kitchen nemesis, the Indian meal moth.

|

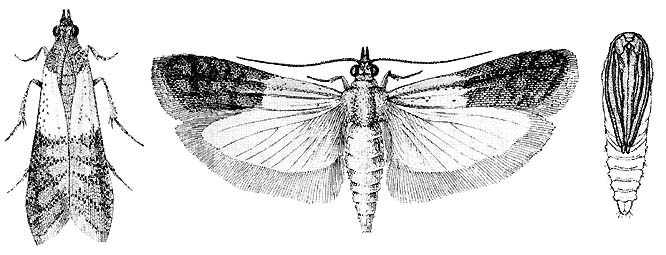

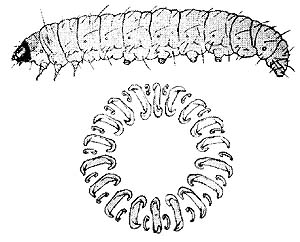

| Plodia interpunctella, adults (wingspan 16 mm) and pupa |

Our tale began almost a decade ago, when my boys were still small and delightful (at least in retrospect). The tiny gray-brown moths began fluttering around my kitchen one day shortly after a trip to my local natural food cooperative. The adults are small, the two-toned front wings divided by a thin irregular line. When the wings are folded at rest, the lighter color is closer the head, the darker color below.

It was the beginning of our acquaintance, and I fear there shall never be an end. For the first half-decade, I didn't care what the name of those unholy flutterers was. I just concentrated on getting rid of them.

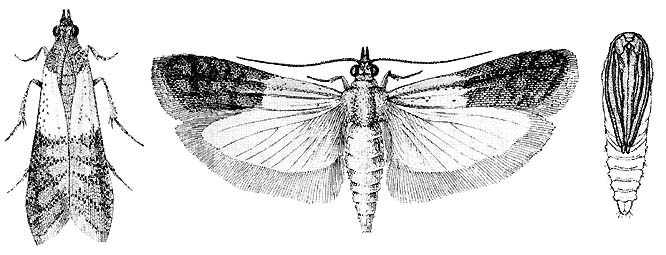

I suspected they must eat grain products, so I'd go through my pantry, one drawer a week, looking for them. Every so often I'd hit it big. I'd find a cereal box, or a bag of wheat germ that exhibited their tell-tale webbing and the small, dirty white larvae. I'd wrap the infested food in several layers of plastic and dump it in the garbage, content to have Cedar Hills deal with the little buggers rather than me.

|

| Plodia interpunctella larva and pattern of "crochet hooks" on proleg |

I was especially concerned when the adults were flying. They have a disconcerting weak, flimsy flight, highly erratic. Despite their seeming frailness, I could seldom catch them. My husband preferred a fly swatter, but he invariably managed to deface the few items of decoration I had set about the kitchen walls. I preferred a two-hand clap, closing in on the moth as it feebly fluttered in the kitchen air. However, most of the time, just as I was about to clap a fatal blow, it fluttered helplessly off in a different direction, its life temporarily spared, repeatedly. Helpless indeed.

I renewed my hunting for larvae more diligently when the adults flew, reminded by them of my lack of good domestic larder management. When they were out of my face, it didn't matter so much. However, as this dragged on, cycle after cycle over the years, I got fairly compulsive about going through everything in less time so that they would have no pantry habitat left.

I found them in absolutely ridiculous places. Once I found a robust colony of hundreds of larvae in a small bag of Morton's salt I used for canning pickles. Salt. Now, I'm no chemistry whiz, but the last time I looked, that was a sodium atom in combination with a chloride atom. Now how on earth could that be food to a bug? There isn't a carbon atom to be had in the whole bag, nor is the breakdown product likely to ever produce a carbon atom. So where did I get the idea food had to have carbon in it?

Another time I found them in a Spice Island spice can. I believe the spice was curry, but I can't be certain any more. At least curry has carbon atoms. Some other big finds come to mind, like the 5 pound bag of bird seed. Or the tupperware container I used to store popcorn kernels (before popping). Or the bag of Niko-niko brand rice. Cereal boxes, cake mixes, the binding of my cookbook, the rose petals I was drying for potpourri; the list goes on. Sometimes I found them just quietly binge-ing away right on my shelves in the corners where residue builds up. I was repulsed. I washed the shelves, using a knife to scrape every last bit of residue out of the corners. Just for the record, I don't use poisons. It's against my philosophy of life. Rather, I embrace long suffering.

I found out quite a lot about the life-style of my moth cohabitants over the years. I found that the larvae have an urge to disperse upward before they pupate. They especially like corners. I can usually tell how we're doing by looking at the ceiling to see how many pupae there are. I also learned that if the larvae don't get much to eat, they can go through their life cycle anyway. The adults are just smaller. Normally, the adult moths are a whopping 1 cm, but I've had adults half that big. You gotta wonder.

There have been long periods - months on end - without moths. Times I've hoped I finally had the upper hand. But they've always rematerialized. Including as I speak. But wait. These recent moths are not two-toned. They are uniformly dingy. The trailing edge of the wing is ragged, not nicely scalloped like the Indian meal moth! That means another species as well. Lucky me, diversity to my long-suffering. Now I don't even know what behavior belongs to what moth! Luckily I haven't been able to eradicate them. There is still opportunity for a few experiments in the kitchen, and another article next year. Vive la science!

Note: According to literature I found, the Indian meal moth is supposed to be a pest of stored grain, nuts and raisins. I guess popcorn, rice, cereal and bird seed could all generally fit under "grain," but no one said anything about salt! Guess you gotta take research with a grain of it.

[Here's some general info from the Handbook of Pest Control: A native of the Old World, the species is a very general feeder, and is recorded infesting chocolate, dog food, and red pepper besides the more usual grain and fruit products. No mention of salt, however. One entomologist wrote "my own residence ...literally swarms with adults, despite the fact I have been unable to find any infested food supply." He should have tried salt! The species overwinters as larvae, which pupate in March and emerge in April. The female, living up to 18 days, lays 200-400 eggs. The larval stage varies a lot with temperature and food, and lasts 13 to 288 days. The larvae are susceptible to the bacterial insecticide BT (as used on gypsy moths!) and to a wasp parasite, Bracon hebetor. There is an "excellent" pheromone trap available for adults. See also Gerry Conley's account of his private battle with Plodia interpunctella.---editor]

References

Mallis, Arnold. 1990. Handbook of Pest Control. 7th edition. Cleveland: Franzak & Foster Co.

This page last updated 16 June, 2005