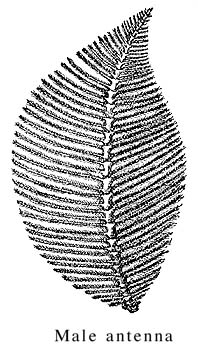

Males have much wider antennae (see below)

BUG OF THE MONTH: July 1994

Polyphemus Moths

Copyright © 1994 by Louise Kulzer

This article originally appeared in Scarabogram, July 1994, New Series No. 171, p. 2.

|

|

|

Polyphemus female, from Holland (1903) Males have much wider antennae (see below) |

Properly Antheraea polyphemus, this giant of a moth is named after the legendary Cyclops of the same name from Homer's Odyssey. (Remember - the fierce one-eyed giant who lived in a cave and tended sheep and ate straying sailors?) These large moths are found in the Puget Sound area, though they are not terribly common; in fact, they're nearly extinct in areas with lots of street lights. When you only have a week to mate and lay your eggs, wasting time circling a light (and making a tempting banquet for bats) is not healthy!

The adult is a velvet-like light brown, sometimes reddish brown, with "watermark" patterns at various parts of the wing, highlighted with whitish, pink and deeper browns. There are four transparent eyespots, one in each of the fore and hind wings. Each eyespot is circled with yellow and black. the lower eye spots are also surrounded by an oval of blue grading from light to a midnight black. Tastefully striking, a fashion writer might say. Adults are 10-12 cm across, definitely big enough to be noticed!

I had the good fortune to be called by a nature-lover on the Kent hill who had found one at her door. She had put it in a plastic container, where it had promptly laid eggs. I went to collect it from her, as she had no interest in keeping it, and I thought the eggs just might hatch. And indeed they did!

The eggs are small, circular, and look like a squashed ball (kind of like a hastily placed peanut-butter cookie before you put the fork marks on it). The eggs hatched in about 10 days to two weeks. Most of the wee small caterpillars shrivelled up and died, but of the 30 or so I placed on leaves, a dozen survived.

Not knowing for sure what moth it was at the time, I placed all the larvae on bitter cherry (Prunus emarginata), but also put a sprig of vine maple in the vase. Polyphemus caterpillars eat maple, whereas Ceanothus caterpillars, Hyalophora euryalis, the other possible identity, eat cherry, among other things. A day later, most of the caterpillars had moved to the vine maple. By that time Scarab Crawford had returned my calls and determined that the moth must by a Polyphemus because of the transparent eyespots. The larvae and Rod had confirmed the ID collaboratively!

I learned the hard way that the larvae have no instincts about water, and several crawled down the stems into the water of the vase, where they perished. After this incident, I plugged the space around the stems with tissue.

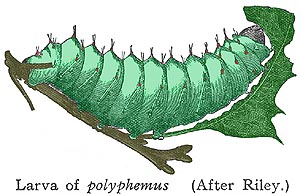

The caterpillars are green and have several rows of tubercles along the body. The tubercles are red tinged with a narrow band of yellow at the base and with black spines sticking out of the top. The front of the caterpillar often is held so that it appears thicker than the "tail end," and the front tubercles are more pronounced than the back ones. In addition, the caterpillar assumes a "hunched" position when at rest, making the fore-body look even larger.

I divided the 12 caterpillars and left six inside to live on vine maple leaf bouquets. I put the other six outside on the vine maple by my door with a bag fashioned from an old gauze curtain around them. It's now three weeks later, and only two of the inside caterpilars are to be seen. I know not where the others went except for two who managed to crawl into the water and drown despite my best efforts. Four of the outside caterpillars made it so far, which includes weathering that big storm in early July.

If we get that far, the cocoon is supposed to be wrapped in a leaf. It is brown, broadly oval and papery looking. If all goes well, the legend of the Polyphemus moth will live again in my Ballard neighborhood, having been passed on from an ancient moth-guardian from Kent (she really was 80, but her gentle spirit is certainly ancient). Wow. Now that's a bug story for you.

References

Holland, W.J. 1903. The moth book. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co.

Villiard, Paul. 1969. Moths and how to rear them. New York: Funk and Wagnalls. [Does not include polyphemus, oddly enough, but good general info on rearing moths].

This page last updated 16 June, 2005