(note form of end of abdomen)

BUG OF THE MONTH: November 1996

The Cat Flea

Ctenocephalides felis

Order Siphonaptera, Family Pulicidae

Copyright © 1996 by Louise Kulzer

This article originally appeared in Scarabogram, November 1996, New Series No. 199, pp. 2-3.

|

| Ctenocephalides felis male (note form of end of abdomen) |

Fleas are relative new-comers in the insect world. Since reptiles don't have fleas, but birds and mammals do, they apparently have evolved after the radiation of the latter groups. [Editor's note: There have been reports of fleas in dinosaur days, but the true identity of these specimens is disputed.] From records preserved in Baltic amber, we know that fleas in their present form have been around at least for 50 million years (Rothschild 1965). Mammals have been around for 180 million. In Rothschild's view, fleas were undoubtedly free-living before they became parasitic.

She speculates that fleas arose from scavenging flies, whose larvae fed on excrement in mammal burrows. So sometime between 180 million years ago and 50 million years ago, the specialization of these dung flies turned into all-out parasitism, and the flea as life-form was cast in chitin (so to speak).

Fleas tend to specialize on a limited number of hosts. For instance, fleas of squirrels don't bother mice, but the same flea species may be found on several species of ground squirrels. The cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis, parasitizes cats, dogs, and in a pinch, other domestic animals including man.

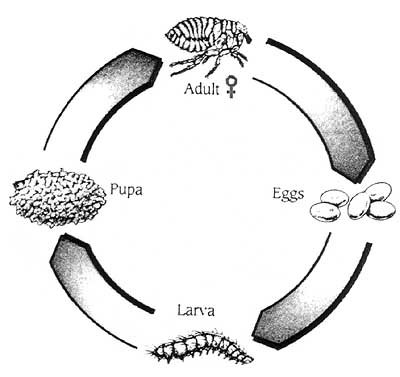

Fleas have complete metamorphosis - that is, the larvae look distinctly different from the adults and have an intermediate pupal stage in which they do their shape-shifting. Adults look sort of like pancakes with legs - huge legs. They are noted far and wide for their ability to jump great distances.

Adults mate on the host and there lay their eggs: in the case of C. felis, on cats and dogs. The eggs, unlike the eggs of head lice, are not cemented to the hair and tend to roll off onto the floor or bedding. The eggs hatch into whitish maggot-like larvae which feed on organic debris, including (but not limited to) the blood-rich excreta from the adults (Rothschild 1965). The larvae are not usually on the cat itself, but in bedding (the cat's or yours, if your cat sleeps with you), carpets and dusty corners (Milne & Milne 1995). When mature, the larvae pupate in cracks and crevices in floors or bedding.

Eggs, larvae, and pupae are all very sensitive to desiccation. The Fleabusters folks use this fact in their control strategy. Fleabusters applies a desiccant to carpets and upholstery that dehydrates and kills the immature stages. Thus any fleas your cat gets will have to be recruited from outside the treated area, putting a real dent in the population. [Other new-tech flea control methods include "Program," a drug the cat takes which prevent fleas biting that cat from reproducing; and "Advantage," a drug applied externally to the cat that kills biting fleas directly without harming the cat. All three systems are effective (also with dogs); what's best depends on your situation.]

But not so fast. Before we bust all our fleas, I've got more to say! Suppose a larva doesn't get dried out but pupates and successfully emerges as an adult in your house. It still has a formidable challenge ahead: to find and attach itself to a cat. How fleas do this is pretty cool.

First, they are able to get in the vicinity of the cat by sensing the warm emanations of carbon dioxide the cat breathes out (Rothschild, 1965). Next they employ their large jumping legs and fling themselves in the direction of the unsuspecting (often napping) cat. Fleas tend to turn over in mid-air when they jump. Clumsy? It has long been know that fleas have large air sacs in the legs. Apparently these air sacs are responsible for the fleas' tendency to tip forward during a jump. They also hold one pair of legs up over their back, claws turned in the direction of travel. Weird? By raising and rotating the legs, fleas can use their well-endowed claws as a sort of grappling hook, ready to dig into the hairy wall of our cat as they hurtle by. Neither clumsy or weird, then - simply a useful adaptation!

Once on the cat, fleas feed by sucking blood. They are active, rather than sedentary like a tick, spending much of their time in motion (Lewis et al. 1988). This is where their pancake-like form comes in handy, ploughing through fur, cruising for "chicks." Speaking of the opposite sex, the sexual cycle of many fleas is regulated by the mammal hormones they imbibe with the blood (egads, spiked blood!). This is well documented in the fleas of the European rabbit (Rothschild, 1965), but probably true for cat fleas as well. So, when your cat's in heat, your cat's fleas may be too!

My, what would mamma say?

References

Fleabusters pamphlet, RX for Fleas.

Lewis, Robert E., J.H. Lewis and C. Maser. 1988. The Fleas of the Pacific Northwest. Oregon State University Press.

Milne, L., & M. Milne. 1995. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects and Spiders. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Rothschild, Miriam, 1965. Scientific American, Volume IV, A Diversity of Life Styles, p. 223 - 232.

This page last updated 16 June, 2005